Perry Carnegie Library History

Presented by Sharon Courtright March 2, 2022

Carnegie Library Progress Club Meeting

* Also known as Perry Progress Club

Carnegie Libraries

Many Americans first entered the worlds of information and imagination offered by reading when they walked through the front doors of a Carnegie library. One of 19th-century industrialist Andrew Carnegie’s many philanthropies, these libraries entertained and educated millions. Between 1886 and 1919, Carnegie’s donations of more than $40 million paid for 1,679 new library buildings in communities large and small across America. Many still serve as civic centers, continuing in their original roles or fulfilling new ones as museums, offices, or restaurants.

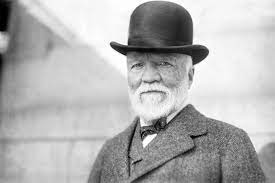

Andrew Carnegie

The patron of these libraries stands out in the history of philanthropy. Carnegie was exceptional in part because of the scale of his contributions. He gave away $350 million, nearly 90 percent of the fortune he accumulated through the railroad and steel industries. Carnegie was also unusual because he supported such a variety of charities. His philanthropies included a Simplified Spelling Board, a fund that built 7,000 church organs, the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, and the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. Carnegie also stood out because some questioned his motivations for constructing libraries and criticized methods he used to make the fortune that supported his gifts.

The First Carnegie Libraries

The first library to be commissioned by Carnegie in the United States was in 1886 in his adopted hometown of Allegheny, Pennsylvania. In 1890, it became the second of his libraries to open in the US. The building also contained the first Carnegie Music Hall in the world.

The first Carnegie library to open in the United States was in Braddock, Pennsylvania. In 1889 it was also the site of one of the Carnegie Steel Company’s mills. It was the second Carnegie Library in the United States to be commissioned, in 1887, and was the first of the four libraries which he fully endowed. An 1893 addition doubled the size of the building and included the third Carnegie Music Hall in the United States.

Initially Carnegie limited his support to a few towns in which he had a personal interest. These were in Scotland and the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area. In the United States, nine of the first 13 libraries which he commissioned are all located in Southwestern Pennsylvania. The Braddock, Homestead, and Duquesne libraries were owned not by municipalities, but by Carnegie Steel, which constructed them, maintained them, and delivered coal for their heating systems.

Until 1898, only one library was commissioned in the United States outside Southwestern Pennsylvania: a library in Fairfield, Iowa, commissioned in 1892. It was the first project in which Carnegie had funded a library to which he had no personal ties. The Fairfield project was part of a new funding model to be used by Carnegie (through Bertram) for thousands of additional libraries.

Beginning in 1899, Carnegie’s foundation funded a dramatic increase in the number of libraries.

This coincided with the rise of women’s clubs in the post-Civil War period. They primarily took the lead in organizing local efforts to establish libraries, including long-term fundraising and lobbying within their communities to support operations and collections. They led the establishment of 75–80 percent of the libraries in communities across the country.

Carnegie believed in giving to the “industrious and ambitious; not those who need everything done for them, but those who, being most anxious and able to help themselves, deserve and will be benefited by help from others.” Under segregation black people were generally denied access to public libraries in the Southern United States. Rather than insisting on his libraries being racially integrated, Carnegie funded separate libraries for African Americans in the South

For example, in Houston he funded a separate Colored Carnegie Library.[10] The Carnegie Library in Savannah, Georgia, opened in 1914 to serve black residents, who had been excluded from the segregated white public library. The privately organized Colored Library Association of Savannah had raised money and collected books to establish a small Library for Colored Citizens. Having demonstrated their willingness to support a library, the group petitioned for and received funds from Carnegie.

Carnegie’s grants were very large for the era, and his library philanthropy is one of the most costly philanthropic activities, by value, in history. Carnegie continued funding new libraries until shortly before his death in 1919.

The Carnegie Formula

Nearly all of Carnegie’s libraries were built according to “the Carnegie formula,” which required financial commitments for maintenance and operation from the town that received the donation. Carnegie required public support rather than making endowments because, as he wrote: “an endowed institution is liable to become the prey of a clique. The public ceases to take interest in it, or, rather, never acquires interest in it. The rule has been violated which requires the recipients to help themselves. Everything has been done for the community instead of its being only helped to help itself.”[23]Carnegie required the elected officials—the local government—to:

- demonstrate the need for a public library;

- provide the building site;

- pay staff and maintain the library;

- draw from public funds to run the library—not use only private donations;

- annually provide ten percent of the cost of the library’s construction to support its operation; and,

- provide free service to all.

Architecture

Architectural criteria included a lecture room, reading rooms for adults and children, a staff room, a centrally located librarian’s desk, twelve-to-fifteen-foot ceilings, and large windows six to seven feet above the floor. No architectural style was recommended for the exterior, nor was it necessary to put Andrew Carnegie’s name on the building. In the interests of efficiency, fireplaces were discouraged, since that wall space could be used to house more books.

There were no strict requirements about furniture, but most of it came from the Library Bureau, established by Melvil Dewey in 1888. It sold standardized chairs, tables, catalogs, and book shelves.

Locations Worldwide

Of the 2,509 Carnegie libraries built between 1883 and 1929, 1,689 were constructed in the United States; 660 in the United Kingdom and Ireland; 125 in Canada and others in Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Serbia, Belgium, France, the Caribbean, Mauritius (officially the Republic of Mauritius, an island nation in the Indian Ocean about 1,200 miles off the southeast coast of Africa) Malaysia and Fiji.

Oklahoma

In Oklahoma, 24 public grants were awarded; and 24 public libraries were built. The total of the grants, awarded from October 27, 1899 to March 31, 1916 was $494,500. An academic library was constructed at the University of Oklahoma with a $30,000 grant given on February 20, 1903.

Distinct Style

At first the Carnegie Corporation did not require that a library be designed by an architect, and no stylistic criteria were attached to the building’s appearance, other than that it should signify the institution’s importance to the community. Carnegie Libraries have distinctive styles; more than half were designed as Classical Revival, often called Carnegie Classical, identified by columns and a large pediment over the main entrance.

Seventeen of Oklahoma’s Carnegies are Classical Revival. While not all bear the Carnegie name in their title, their appearance generally indicates their genesis.

Great Depression Impacts

Unfortunately, the onset of the Great Depression impacted most local economies throughout the state, and there was little money for libraries. As the New Deal made money available in the 1930s, some cities applied for Works Projects Administration funds to repair or expand existing facilities. In Oklahoma the WPA constructed ten new libraries, reconstructed, or repaired five, and built additions to two. Most WPA library “reconstruction” projects resulted in the total obliteration of the library’s original architectural style, generally replacing it with the trendy Art Deco or Moderne styles, and “addition” projects did the same.

Libraries in Oklahoma Still Standing or Razed

Of Oklahoma’s twenty-four Carnegie Libraries, seventeen still stand, in various states of alteration: Ardmore, Bartlesville, Collinsville, Cordell, Elk City, El Reno, Frederick, Guthrie, Hobart, Lawton, Muskogee, Perry, Sapulpa, Shawnee, Tahlequah, Wagoner, and Woodward. Of the seventeen, only nine are still libraries: Collinsville, Elk City, El Reno, Frederick, Hobart, Perry, Sapulpa, Tahlequah, and Wagoner. The others serve as museums, offices or meeting places.

Razed buildings include Chickasha, Enid, McAlester, Miami, Oklahoma City, Ponca City, and Tulsa.

The Ardmore, Cordell, El Reno, Guthrie, Hobart, Lawton, and Tahlequah libraries are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Perry Carnegie Library’s Story

Library Built in 1909 with Carnegie Foundation Grant

Perry’s Carnegie Library was constructed in 1909 with funds from a $10,000 grant from the Andrew Carnegie Foundation.

Perry's First Library 1902

Perry’s first library was one room with a restroom, located on the north side of the square, provided in 1902 by members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

The WCTU struggled, not only to provide books and decent literature for children and adults of the community, but also for chairs, tables and other furnishings. The group solicited funds and books from friends for two years, but by 1904 were about ready to give up the effort. At that time, the WCTU reading room had only about 400 books and some temperance literature.

Perry Library Association & Ladies' Clubs

Rather than see the project fail, the WCTU turned to the three Ladies Literacy Clubs of Perry for help. The group received an immediate positive response and in April of that year a mass meeting was held for women of the community for the purpose of considering the question of organizing a library. As a result of the meeting, the Perry Library Association was formed.

The Ladies Tuesday Afternoon Club, Perry Progress Club and the Coterie Club provided support in the way of books, magazines and furnishings.

Virtually, no public funds were available, but the club women organized themselves to guide the project. A board of directors and officers were elected, and membership was opened to anyone interested, men included. Mrs. M.A. Lucy, who later served as librarian, was elected president.

Early Days & The First Library Board Meeting

At the first meeting, the group decided to rent rooms on the second floor of Judge Hainer’s new building on the northwest corner of the square at $8 per month, including janitor service.

There was no money to hire a librarian, but women took turns keeping the facility open by volunteering to serve brief shifts each Wednesday and Saturday. Most books were acquired through donations and occasional ice cream socials and other benefits were held to raise funds to add other books to the shelves.

First Paid Librarian 1904

In September, 1904, the board decided that longer hours of operation were needed. However, this created scheduling problems for volunteers. The board then created a salaried position with pay set at $3 per week and hours of operation were set at 7:30-9:30 p.m. Miss Lola Brisoe was appointed librarian in December, 1904 and she served in that position for six months.

Dreams of a New Library

The association had its eye on a portion of vacant land in the courthouse park as the site for a city library, although members knew this dream would not be realized soon.

Perry’s city officials provided the first public funds for library purposes in 1906, a one-mill tax levy….over the protests of A.E. Smyser, Perry’s mayor at the time. Smyser objected on the basis that water lines, sewer extension and fire protection should have priority.

In 1908, Ms. H.L. (Lucy) Boyes was appointed by the association president, Ms. B. L. Hainer, to look into the possibility of securing the southwest corner of the square, which was government property, as a library building site.

Mrs. Boyes sought assistance from Congressman Bird S. McGuire, a Perry attorney, in obtaining the land.

Within three months, on July 3, 1908, the library board received a government patent for the land. ***Women get things done, right?

Now, the women were faced with obtaining money for construction. Again, Ms. Boyes was up to the challenge for this phase of the library effort. A committee was formed to contact Andrew Carnegie, Scottish immigrant and steel magnate, who had established a foundation for such purposes.

Construction Funds - 1907 Carnegie Foundation Grant

In 1907, the foundation awarded a $10,000 grant for the purpose of constructing a library in Perry. The grant proved to be the exact amount, to the penny, necessary for the construction of Perry Carnegie Library.

However, there would be another hurdle regarding construction funding. In the Carnegie contract with Perry, there was a stipulation that the building was to be used for no other purpose but a library and the city council had to pass a resolution pledging an yearly appropriation of one mill to support the library. The resolution passed unanimously and $10,000 was placed with the Hoboken Trust Company, subject check of the building committee as work progressed.

The Building Committee, Contractors, and Architects

The building committee was headed by Charles Christoph, chairman, and Ms. J. H. Bullen, Ms. H. L. Boyes, Major John Jensen and E. E. Howendobler. A.C. Kreipke of El Reno was the contractor and architects were Layton, Wemyss, Smith and Hawk of Oklahoma City.

1910 Dispute Between the Mayor and the Committee

After the building committee accepted construction of the building on May 21, 1910, there was a surprising, but bitter standoff between the committee and then Perry Mayor James Lobsitz, who thought the building should not house only a library but new city headquarters as well. The building committee would not agree because this plan was not in line with the requirements set forth in the grant agreement.

Lobsitz, who owned a hardware store in Perry, changed the lock on the library door. This took place after a confrontation involving Lobsitz, a diminutive man of about 5’ 4” and the building committee chairman, Charles Christoph, who towered over the mayor by at least a foot.

Miss Irene McCune, 18, who later married Ralph W. Treeman, had enjoyed her position as librarian in the new building for only a few months when the door lock was changed and she could no longer enter the building to perform her librarian duties.

Library board members located a small, unlocked window in the furnace room and asked Miss McCune to enter the building this way and continue to conduct business. She was willing, but her father, L. W. McCune, forbid her to do so, telling her that her salary of $15 per month was hardly enough to justify that kind of unladylike behavior.

Because of the dispute, a lawsuit was filed in district court and until the case was decided, library patrons were not permitted to enter the building, but could request books to be brought to them outside and the books could be returned in the same manner. The Supreme Court eventually ruled the mayor was wrong, the library settled into a more peaceful routine and a truce was called between Mayor Lobsitz and the building committee.

The Perry Library is Still a Carnegie Library

Unlike some Carnegie Library buildings that were razed in favor of newer, more modern structures, our library building has undergone renovations and adhered to the original grant contract that it be used only for library purposes…a major renovation was done in 1990 and over the years other, less major improvements have continued.